Discworld vs Good Omens vs Hitchhiker's Guide: Which Should You Read?

Comparing Terry Pratchett's Discworld, Good Omens, and Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker's Guide. Find the perfect humorous fantasy or sci-fi series for your reading style.

Discworld vs Good Omens vs Hitchhiker's Guide: Which Should You Read?

You want something funny. Not sitcom-funny—properly, brilliantly funny, the kind of book that makes strangers on the train stare at you because you just snorted into your coffee. You've narrowed it down to three names that keep appearing in every recommendation thread: Terry Pratchett's Discworld, Pratchett and Neil Gaiman's Good Omens, and Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

All three are beloved. All three are hilarious. And they're different enough that the one you pick first will shape how you feel about the others.

Here's the honest guide to choosing between them—what each one does best, what might frustrate you, and where to start depending on who you are as a reader.

The Thirty-Second Version

| Discworld | Good Omens | Hitchhiker's Guide | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Terry Pratchett | Pratchett & Neil Gaiman | Douglas Adams |

| Setting | Fantasy (flat world on a turtle) | Modern-day England | Science fiction (the galaxy) |

| Books | 41 novels | 1 novel | 5 novels (a "trilogy") |

| Tone | Warm, humanist, satirical | Clever, apocalyptic, charming | Absurdist, nihilistic, razor-sharp |

| Best for | Character depth, social commentary | A perfect standalone read | Pure comedic craft |

| Commitment | Low per book, high for the series | A single weekend | Moderate (5 short books) |

Still not sure? Keep reading.

What Each Series Actually Is

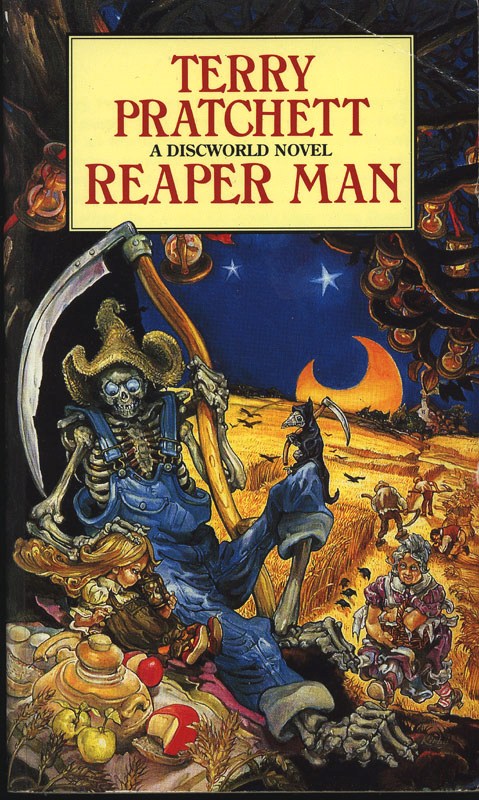

Discworld: 41 Books of Humanity on a Turtle

Terry Pratchett's Discworld is a flat world balanced on four elephants standing on a giant turtle swimming through space. That's the setup. What it actually is: a forty-one-book exploration of everything that makes humans human—greed, love, justice, prejudice, death, taxes, and the postal service.

"Pratchett isn't laughing at humanity. He's laughing with it, even when it's being terrible."

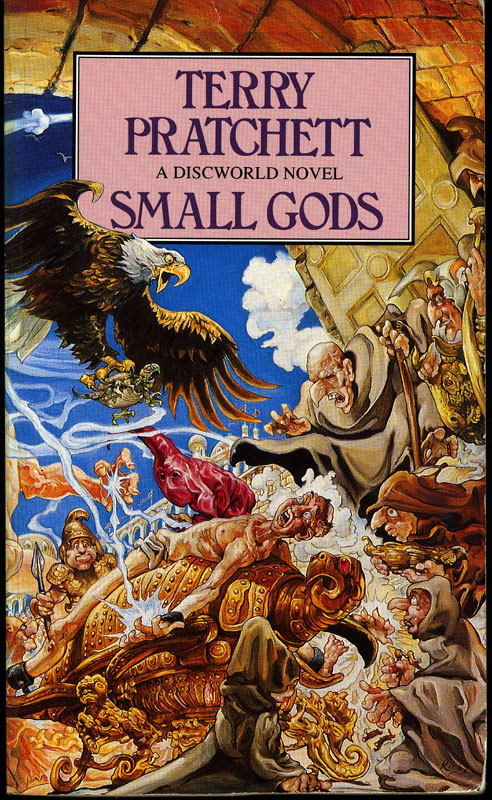

The series spans everything from police procedurals (the City Watch books) to philosophical meditations on religion (Small Gods) to coming-of-age stories about a young witch on the chalk downs. There's no single genre—each sub-series has its own flavour. What connects them is Pratchett's voice: warm, furious, funny, and deeply compassionate.

Pratchett isn't laughing at humanity. He's laughing with it, even when it's being terrible. His satire has teeth, but it also has a beating heart. You finish a Discworld book feeling like the world is messy but worth fighting for.

Good Omens: The Apocalypse, But Make It British

Good Omens is what happens when Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman write a book together about the end of the world. An angel (Aziraphale) and a demon (Crowley) have been living among humans for six thousand years and have grown rather fond of them. When the Antichrist is born and Armageddon approaches, they decide they'd rather it didn't happen, thank you very much.

It's a buddy comedy wrapped in religious satire wrapped in a love letter to Southern England. The humour falls somewhere between Pratchett's warmth and Gaiman's darkness—funnier than most Gaiman, darker than most Pratchett. If you've seen the Amazon series, the book is sharper and stranger.

One book. One perfect, self-contained story. No sequels to worry about, no reading orders to research.

Hitchhiker's Guide: The Universe Doesn't Care (And That's Hilarious)

Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy begins with the Earth being demolished to make way for a hyperspace bypass. Arthur Dent, still in his dressing gown, is rescued by his friend Ford Prefect—who turns out to be an alien researcher for the titular Guide. What follows is a journey across the galaxy that's less about plot and more about Adams finding the funniest possible way to describe the meaninglessness of existence.

Adams writes like nobody else. His sentences are precision instruments of comedy—every word calibrated for maximum impact. The answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything is 42. The most useful item in the galaxy is a towel. A whale materialises above a planet and has a brief, poignant existential crisis before impact.

"Adams writes like a watchmaker who makes watches that tell jokes instead of time."

Where Pratchett is warm, Adams is cool. Not cold—there's genuine affection in his writing—but his comedy comes from distance. He's standing far enough back to see the absurdity of everything, and he reports on it with the detached amusement of someone writing a particularly sardonic travel guide.

How the Humour Differs

This is really what it comes down to. All three are funny, but they're funny in fundamentally different ways.

Pratchett's humour is empathetic. He creates characters you love—Sam Vimes, Granny Weatherwax, Death—and then puts them in situations that are simultaneously absurd and deeply real. The laughs come from recognition. When Vimes arrests two opposing armies in Jingo, it's funny because you can see exactly the kind of stubborn, principled person who'd try it.

Adams' humour is observational. He looks at the universe and describes it so precisely that the absurdity becomes obvious. His jokes are about the gap between how things are and how things should be—bureaucracy, technology, language, existence itself. You laugh because he's right.

Good Omens' humour is collaborative chaos. It has Pratchett's character warmth and Gaiman's flair for the gothic, held together by a shared love of absurdity. The Antichrist is an eleven-year-old boy in a small English village. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse ride motorbikes. An angel's greatest fear is losing his rare book collection. The comedy comes from the collision of the cosmic and the mundane.

Here's another way to think about it. Imagine all three authors walk into a terrible restaurant:

- Pratchett writes about the waiter who's been working there for thirty years and still believes, against all evidence, that today might be the day things improve

- Adams writes a perfectly structured paragraph about how the restaurant's existence proves that the universe has a malicious sense of humour

- Pratchett and Gaiman together write about the angel who insists the food is "actually rather nice" while the demon silently questions six thousand years of friendship

The Emotional Spectrum

Here's where the differences get sharper.

Discworld will make you cry. Not every book—probably not even most books. But Night Watch will. The Shepherd's Crown will. These are books that earn their emotional moments because Pratchett spends entire novels making you care about people before he puts them through the wringer. The darkness in Discworld is real—revolution, persecution, grief—but so is the hope.

Hitchhiker's Guide will make you think. Adams was interested in big questions—the meaning of life, the nature of consciousness, why Mondays are terrible—and he explored them through comedy. You won't cry reading Adams, but you might stare at the ceiling for a while afterwards, wondering whether the universe really is as absurd as he makes it seem. (It is.)

Good Omens will make you believe in people. Despite being about the literal apocalypse, it's fundamentally optimistic. Humans are weird, messy, and contradictory, and that's exactly why they're worth saving. It's the most feel-good apocalypse you'll ever read.

The Commitment Question

This matters more than people admit.

Good Omens: One book. About 400 pages. You can read it in a weekend. No sequels, no reading orders, no "but you have to get through the first three before it gets good." It's the lowest-commitment option by a mile.

Hitchhiker's Guide: Five books (Adams called it "a trilogy in five parts" because of course he did). They're all short—you could get through the whole series in a week or two. The first book is self-contained enough that you can stop there if you want, though the quality does get uneven. So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish is divisive. Mostly Harmless is bleak in a way that catches people off guard.

"You can read any Discworld book without having read the others. Forty-one books sounds like a commitment. It's actually forty-one entry points."

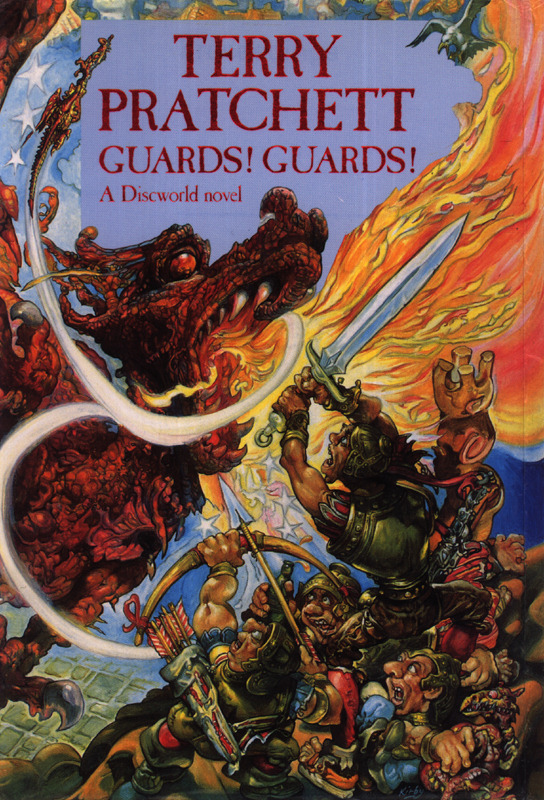

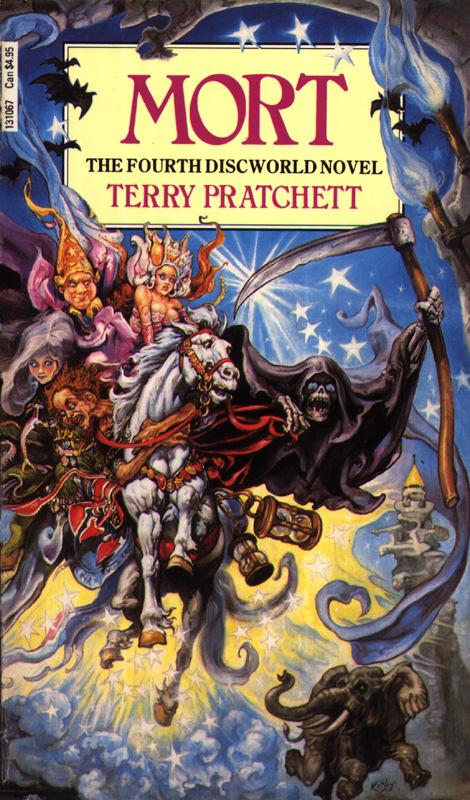

Discworld: Forty-one books sounds terrifying. Here's the secret: you don't read them all. You pick a starting point—Guards! Guards!, Mort, or Small Gods are the usual recommendations—and follow whatever thread interests you. Each book is self-contained. You can read five and stop, or read all forty-one over a decade. Nobody's checking. Check out our guide to where to start with Discworld if you want specific recommendations.

Who Should Read What

Start with Good Omens if...

- You want a single, perfect book with no commitment

- You love the idea of an angel and a demon as best friends

- You've seen the Amazon series and want the original story

- You're not sure you even like fantasy or sci-fi

- You want something that feels like a warm hug during the apocalypse

Start with Hitchhiker's Guide if...

- You love wordplay, wit, and perfectly crafted sentences

- You prefer science fiction to fantasy

- You enjoy absurdist humour (Monty Python, Catch-22)

- You want something you can finish quickly

- You like your comedy with a side of existential dread

Start with Discworld if...

- You want characters you'll think about for years

- You love satire that actually says something

- You enjoy police procedurals, political thrillers, or coming-of-age stories

- You want a series you can live in for months or years

- You prefer your comedy with a beating heart

The Crossover Question

Here's what people really want to know: if I like one, will I like the others?

Usually, yes. These three sit in the same neighbourhood of literature—funny, clever, British (or British-adjacent)—even if they live on different streets. The vast majority of people who love one will at least enjoy the others.

But there are exceptions:

- If you love Adams' precision but find Pratchett too discursive, that's a real taste difference. Pratchett meanders; Adams economises. Both are deliberate choices.

- If you love Pratchett's character depth, you might find Adams' characters thin. Adams' people are vehicles for ideas. Pratchett's people are people.

- If you love Good Omens' collaborative energy, you might find solo Pratchett too angry in places and solo Adams too detached.

None of these are criticisms. They're differences. Knowing them helps you pick the right starting point.

Our Recommendation

If you've never read any of these and you're standing in a bookshop right now:

Pick up Good Omens. It's one book. It's brilliant. It'll take you a weekend. And it'll tell you immediately whether you lean more Pratchett (characters, heart, social commentary) or more Adams-adjacent (wit, structure, cosmic absurdity). Then follow that instinct.

If you already know you want a series to sink into: start with Discworld. Specifically, start with Guards! Guards!. It has the broadest appeal, the best long-term payoff, and it introduces you to Ankh-Morpork—the city that makes the whole Disc feel alive.

If you want something short, sharp, and quotable: start with The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. The first book is nearly perfect. Just don't judge the whole series by the later entries.

Want to dive deeper into Discworld? Check our beginner's guide, explore the philosophical Discworld books, or discover Discworld's darkest novels.