Moist von Lipwig: Terry Pratchett's Most Underrated Character

Why Moist von Lipwig deserves more recognition as Discworld's most compelling anti-hero, and why his industrial revolution trilogy is essential reading.

Moist von Lipwig: Terry Pratchett's Most Underrated Character

Ask any Discworld fan to name their favorite character, and you'll hear the same names over and over. Sam Vimes. Granny Weatherwax. Death. Maybe Rincewind if they're feeling nostalgic.

What you probably won't hear is Moist von Lipwig.

And that's a shame. Because the fast-talking conman who gets sentenced to death and ends up running the postal service—then the bank, then the railway—might be the most interesting protagonist Pratchett ever created. He's certainly the most modern.

"He was a con artist who conned himself into becoming a hero."

Here's the thing about Moist: he doesn't believe in anything. Not really. Not the way Vimes believes in justice or Granny believes in right and wrong. Moist believes in the con, in the angle, in the beautiful elegance of making people want to give you their money. He's what happens when a sociopath discovers he has talents that society actually needs.

And that makes him fascinating.

Why Moist Gets Overlooked

There's a reason Moist von Lipwig doesn't top those favorite character lists. Several reasons, actually.

He's designed to be forgettable. Literally. Pratchett describes him as having no distinguishing features—the kind of face you can't quite remember five minutes after meeting him. That's intentional. It's part of what made him such a good con artist. But it also means he doesn't stick in readers' minds the way a six-foot-two angry duke's son or a tiny witch with a personality like a granite cliff does.

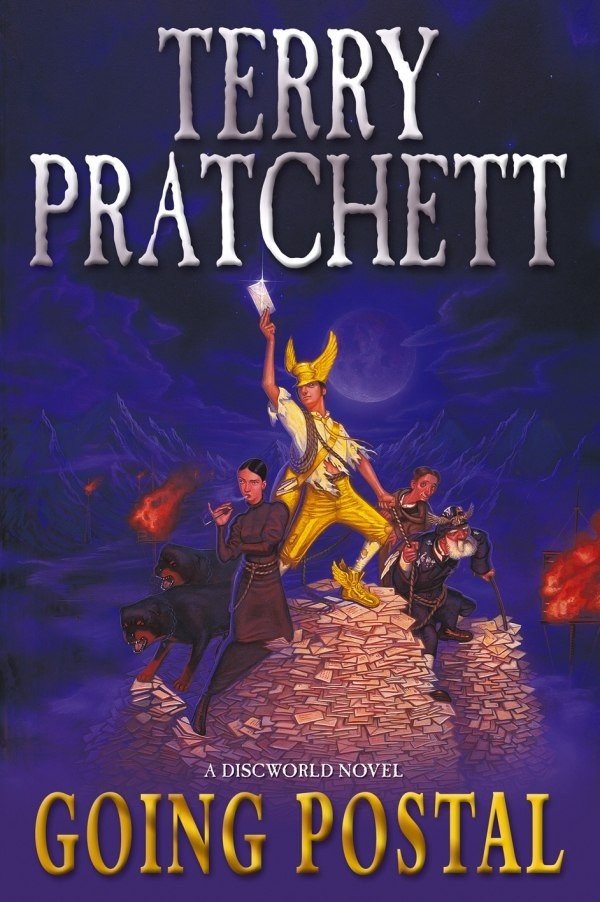

His books came late. Going Postal was published in 2004, the 33rd Discworld novel. By then, fans had already chosen their favorites. The Watch books had established Vimes. The Witches had claimed their territory. Death had become beloved. Moist was the newcomer, arriving at a party that had been going for twenty years.

He's morally ambiguous in uncomfortable ways. Vimes is angry about injustice—we like that. Granny is stern but secretly kind—we understand that. Moist is a man who, as he slowly realizes throughout Going Postal, is responsible for deaths. Not through violence—through fraud. Through schemes that left people bankrupt. Through cons that destroyed lives in ways that never felt real to him at the time.

That's harder to root for, even when he's trying to be better.

The Anti-Vimes

The literary critic Michelle West described Moist as "the anti-Vimes," and that's exactly right.

Where Vimes fights against his darker impulses—the beast inside him that wants to hurt people who deserve hurting—Moist struggles with something different. He fights against his fundamental inability to take anything seriously. To believe in anything beyond the next clever trick.

"He was good at faces. He had a forgettable face."— Going Postal

Vimes became a better man by committing to principles he already believed in. Moist becomes a better man by discovering he has principles at all.

That's a harder story to tell, and a harder one to love. But it's also a more relevant one for many readers. Not everyone relates to the righteous anger of a police commander. But most of us know what it's like to drift through life without quite believing in what we're doing, to realize one day that our choices have consequences we never really considered.

Moist's journey is the journey from nihilism to meaning. And Pratchett tells it brilliantly.

The Moist Trilogy: What Makes It Special

Let's look at what Moist actually does across his three novels.

| Book | Year | Institution | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Going Postal | 2004 | Post Office | Redemption vs. Corporate Greed |

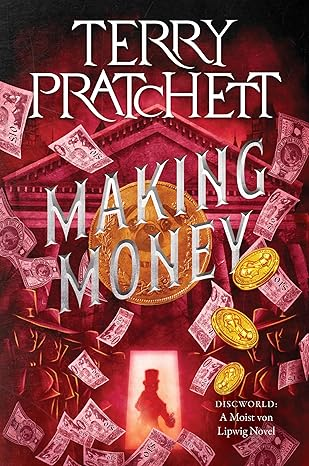

| Making Money | 2007 | Royal Bank | The Illusion of Value |

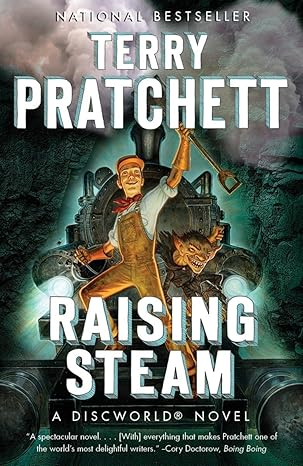

| Raising Steam | 2013 | Railway | Progress vs. Tradition |

Each book follows a similar pattern: Lord Vetinari manipulates Moist into taking over a failing public institution, Moist uses his con artist skills to save it, and along the way he discovers that legitimate work can provide the same thrill as the con.

But within that pattern, Pratchett explores something remarkable: Discworld's industrial revolution.

Going Postal: The Con Artist Finds a Cause

Going Postal opens with Moist being hanged. He survives—barely—because Vetinari has plans for him. The choice is simple: run the decrepit Post Office, or walk into a nice dark room with no door.

Moist takes the job. Not because he believes in it, but because he likes being alive.

What follows is one of Pratchett's best plots. Moist must compete with the Grand Trunk, a telegraph-like communication network run by the villainous Reacher Gilt—a man who is, essentially, what Moist would have become if he'd thought bigger. Gilt is Moist without conscience or limits. He's bought a vital piece of public infrastructure and is running it into the ground while extracting every possible penny.

Sound familiar? Pratchett was writing about private equity firms destroying public services before it became fashionable.

But the book's real heart is Moist's discovery that running a legitimate organization can be just as thrilling as running a con. The Post Office becomes his canvas. He introduces stamps. He brings back the old postmen. He creates spectacles and events and publicity that make people believe in mail again.

And somewhere in the middle of all that, he falls for Adora Belle Dearheart, whose family built the Grand Trunk before Gilt destroyed them. She sees through his charm immediately. She might be the only person who does.

Making Money: The Illusion at the Heart of Economics

"The value of money is the belief that it has value."

In Making Money, Vetinari gives Moist the bank. Not asks—gives. The chairman's dog leaves him 50% of the shares, and suddenly the con artist who used to steal money is responsible for creating it.

This is Pratchett at his most economically literate. The book is essentially a meditation on what money actually is—a collective agreement, a shared belief, a con so large and so old that nobody remembers it started as a con.

Moist, naturally, is perfectly suited to understand this. He's spent his life trading in belief and confidence. Now he's doing it with the full weight of government behind him.

The villain this time—Cosmo Lavish, obsessed with becoming Vetinari—isn't as memorable as Reacher Gilt. But the book makes up for it with its exploration of golems, paper money, and the fundamental strangeness of economic systems. Moist doesn't just save the bank; he invents a new form of currency, because that's what the con artist does when given legitimate tools.

Raising Steam: The Last Adventure

Raising Steam was published in 2013, when Terry Pratchett was deep into his struggle with Alzheimer's disease. You can feel it in the prose—it's more meandering, less tightly plotted, sometimes drifting from scene to scene without the usual Pratchett precision.

But it's also a love letter to progress itself. The railway comes to Discworld, and Moist is there to help it succeed. Goblins gain recognition as persons. Dwarfish extremists attempt terrorism. And through it all, Moist—older now, more settled—does what he does best: he makes people believe.

It's not his strongest book. But it's a fitting end to his arc, showing a man who finally has something he believes in: the future, messy and complicated and full of change.

Why Moist Matters

Here's what makes Moist special, and why I think he deserves more recognition:

He's the most modern Discworld protagonist. Vimes is fundamentally a Victorian figure—the honest copper fighting corruption in the streets. Granny is ancient wisdom given form. Death is, well, timeless. But Moist is a creature of late capitalism, a man who understands that perception is reality and brand is everything. He'd be right at home on LinkedIn.

His redemption feels earned. Pratchett doesn't let Moist off the hook easily. In Going Postal, the golem Mr. Pump forces Moist to confront the fact that his cons killed people. Not directly—but does that matter? Moist has to reckon with what he's done, and that reckoning shapes everything that follows.

He channels dark impulses into productive ends. Moist never stops being a con artist. He just starts conning people for good causes instead of bad ones. His marketing schemes for the Post Office are exactly the kind of manipulation he used to steal money—except now they're making people excited about mail delivery. Pratchett understood that you don't change who you are; you change what you do with it.

His relationship with Adora Belle is the most adult in Discworld. No swooning, no grand romantic gestures. Two damaged people who see each other clearly and choose to stay together anyway. She smokes like a chimney and works to free golems from slavery. He lies compulsively and needs danger like oxygen. They work.

The Bottom Line

Moist von Lipwig isn't the most beloved Discworld character, and maybe he shouldn't be. He's not as immediately likeable as Vimes, not as formidable as Granny, not as philosophically profound as Death.

But he might be the most relevant.

"You can use your talents for good or ill. The talents don't change—you do."

We live in an age of con artists. Of people who've figured out that confidence and branding can substitute for substance, that perception is more important than reality, that the best lies are the ones people want to believe. Moist von Lipwig is what happens when one of those people discovers conscience—or has conscience discovered for him, by a Patrician who needs his skills.

He doesn't become a good person because he stops being a con artist. He becomes a good person because he starts conning people into better institutions, better beliefs, better versions of themselves.

That's a message worth remembering.

Ready to meet Discworld's greatest conman? Start with Going Postal, or check out our guide to Where to Start with Discworld for more entry points.